Norfolk Underwater: Lost Time

How the Army Corps of Engineers Left Black Neighborhoods Out of Norfolk’s Storm Resiliency Plan

by Morgan Norris

The city has asked the Norfolk District of the United States Army Corps of Engineers to include the south side in a feasibility study for flood mitigation. Congress has yet to appropriate any money for the review. Black, low-income communities on the other side of the Elizabeth River remain more vulnerable than the rest of Norfolk to future floods.

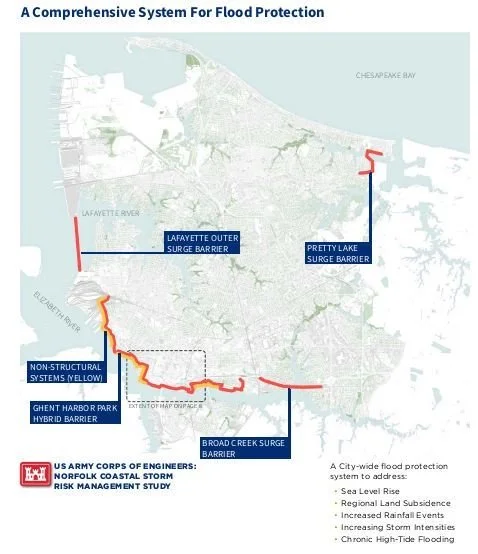

Among U.S. cities, Norfolk is second only to New Orleans in flood risk, which is why the Norfolk City Council approved a partnership with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in April 2023 for the Coastal Storm Risk Management project, a $2.6 billion plan for miles of floodwalls and levees, gates and pumping stations designed to protect the city from hurricanes and other storms supercharged by Climate Change.

But what amounted to the largest infrastructure project in the city’s history would have done nothing to protect historically Black communities on the south side of the Elizabeth River. So, three months later, the City Council passed a resolution asking the Army Corps to study adding Berkley and other predominantly Black Southside neighborhoods.

Now, more than a year later, no money has as yet been appropriated for the three-year study, a lapse environmental justice advocates say speaks of an ongoing failure to protect the city’s Black neighborhoods from flooding and other disproportionate burdens they’ve shouldered for decades from redlining, a lack of infrastructure, pollution and, most recently, accelerating climate change.

Norfolk and the state of Virginia agreed to fund 35 percent of the cost of the Coastal Storm Risk Management (CSRM) project with the Biden administration’s Justice40 pledge in place: 40 percent of all federal investment in climate change, clean energy, affordable housing, environmental protection, and clean water and wastewater infrastructure would go to disadvantaged communities “marginalized by underinvestment and overburdened by pollution.”

Yet, the Army Corp’s Coastal Storm Risk Management project does not reflect this 40 percent funding commitment, and Kim Sudderth, a Berkley resident who is Black and serves as vice chair of the Norfolk Planning Commission, said that to date the city has received no Justice40 benefit. As for future spending, Justice40 is almost certain to be ended by the incoming administration of President-elect Donald Trump, and with the Republican Party now in control of both houses of Congress, funding for the Norfolk study is most likely more doubtful than ever.

Berkley’s Champion

Sudderth holds Berkley near and dear to her heart. She lives there and watches the people she loves be passed over repeatedly. Sudderth knows she has a tricky last name. So, she tells everyone to think of sudsy water and planet Earth. She takes pride in the aloe, pecans, peaches, and other foods she can grow in her backyard.

“I was raised in Oceanview, but as soon as I found Berkeley, I got here as fast as I could,” said the community leader, touching the blue and white patterned wrap around her hair. “Some folks have lived here for decades and have deep roots attached to this place. Berkeley is the center of the universe.”

She loves what she calls the “porch culture” around the neighborhood. On a recent morning, her neighbor Ms. Patsy called her name and wished her a good day. “If I have a meeting to attend, I try to leave my house a good 1-0 minutes early,” said the mother of three. “I end up having a conversation before I even get to my car.”.

As the planning commission’s vice chair of the Norfolk Planning Commission and a member of the Berkeley Historical Society, Sudderth was angered by Berkely’s exclusion from the Coastal Storm Risk Management project.

“It was a logical decision if you’re a bean counter,” said Sudderth, referring to the low property values in Berkeley which make it ineligible for the cost-benefit ratio utilized by the corp of engineers in designing the project.

Left Vulnerable to the Future Storms

After Hurricane Sandy in 2012, Congress passed the Disaster Relief Appropriations Act, which required the Army Corps to execute a project performance evaluation report to address flood risks in affected coastal areas. The city of Norfolk was identified as one of the nine focus areas requiring an “investigation into potential coastal storm risk-management solutions.” The federal funding for the CSRM would pay for almost nine miles of storm surge barriers, 11 tidal gates, and 10 stormwater pump stations to reduce storm risk in a city that is already the most threatened by sea level rise on the East Coast. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration projects that Norfolk will have between 85 and 125 days of so-called “sunny day” flooding by 2050, without even considering the threat of storm surge from hurricanes intensified by Climate change.

Last year, when Norfolk submitted a federal request on behalf of the historically Black communities to be included in the project, the request was approved without funding.

“That would have been a longshot considering the request was submitted late in the process,” said Michelle Hamor, the Army Corps of Engineers Norfolk district’s planning and policy chief.

Even before the election, Hamor said that Norfolk would have to look for an opportunity to have its representatives in Congress place an earmark for the $3 million study in an appropriations bill. “So those are opportunities,” she said. “What will be very important is that appropriations bill. Right now we are in a continuing resolution, and our hope is that it will not be the entire year, and later, maybe early spring, we'll see an appropriations bill which will allow the other funding to take place.”

Hamor said she understands the frustration of community leaders like Sudderth over delays and uncertainty in funding the study. “We apologize for not coming forth to let them know when the work plan was not funded,” she said.

“It's kind of heartbreaking to think that we won't get protected, but we can literally look across the river and see a wall that we can't have,” said Sudderth

Skip Stiles, a senior advisor at the nonprofit Wetlands Watch has been sounding the alarm over climate change since 2006. Stiles enjoys watching sunrises and sunsets over Norfolk waters. The city depends on his emails to know when and where floods will occur.

“It was the prehistoric time when everyone heard us and said ‘What are you talking about?’” said Stiles, as he fixed the collar of his signature plaid flannel. “Once they realized wet angry people also vote for them, people started listening to us.”

Stiles met Sudderth through Mothers Out Front, a growing national movement of mothers mobilizing for a sustainable future for all children. They’ve been good friends ever since and both remember struggling to make climate change a priority in local officials’ agenda.

“There was a time in the state legislature where we weren't even allowed to say flooding in the general assembly,” said Sudderth. “I don't think it got the attention early enough on a state level to address the problem.”

Stiles believes the problem lies within the city planning to mitigate flood risk in general. He believes the federal funding for the CSRM Plan came at a time when Norfolk was not ready.

“What I never see from Norfolk is a strategy allocating money so people have an idea of what’s coming instead of saying, ‘Oh! Here's some federal money, so let’s build a floodwall,’” said the elder advocate. “Let the community make a decision about where their money is going.”

Some of the other cities in Hampton Roads have created plans for flood risk. Virginia Beach implemented The Ripple Effect in 2023, which improved drains, prevented pooling water in streets, and installed tide gates to protect the city. Hampton, Virginia, has implemented the Home Elevation Program and the Floodplain Zone District Ordinance to protect homes from high flood levels and require that all developments in the floodplain meet guidelines to include flood protection.

Stiles believes Norfolk is “a victim to their success” with the swiftness of federal funding with no comprehensive plan. He says this is a domino effect that hurts the vulnerable communities whose homes will be in jeopardy as flooding worsens in the future.

“This is all going to be wetlands again in 2050 or 2060,” said the environmental advocate as he pointed to the current wetlands of Myrtle Park. “You can’t expect people to go couch-surfing or expect all the kids that go to Booker T. Washington High School for their education.”

Long-suffering Communities

Children who attend Booker T. Washington High School experience dangerous levels of flooding. They often have to reroute, and it is harder for younger children whose heights are dangerous for the flood levels.

“It takes days for the water to go down,” said Kenya Gayden. “I always have to review the change in routes to my daughter every time it floods to make sure she remembers and doesn’t get lost walking to Booker T. for school.”

Gayden is a mother of one daughter in Calvert Square, one of the low-income public housing units in Norfolk. She feels like the city dehumanizes low-income communities and believes there is only one way Norfolk can fix the relationship.

“Come out here and assess it!” Gayden screams as she simultaneously watches her only child board the county bus to the grocery store. “All they have to do is come out and see it. There is no way that we have to live like this until something is done, which is God knows when.”

Calvert Square sits next to Tidewater Gardens, a recently bulldozed public housing community north of the Elizabeth River undergoing the St. Paul’s Transformation Project starting in 2021. The project will transform the village into a mixed-income community by daylighting a creek and raising the base elevation to mitigate flood risk. Officials say Calvert Square, however, is not a part of the program.

“I can’t speak to that,” said Mark Matel, senior project manager with the Department of Housing and Community Development. “Tidewater Gardens was formerly owned by the Norfolk Redevelopment Housing Authority (NRHA), and the city is taking ownership of the project. The housing over there is solely the NRHA’s responsibility.”

The most recent update from the NRHA is that they are “planning to plan,” according to WHRO, in June. As of November, they declined an interview after initially agreeing, saying they’re “not ready.”

“We’re still in the preliminary stages of planning,” said Leha Bird, the director of communications. “We just want to keep planning and not make any more statements.”

Norfolk Underwater

Councilwoman Andria McClellan has been on the city council since 2016. She can talk freely about where the city has triumphed and fell short.

“It’s always a bit of a balancing act,” said the co-author of Norfolk’s climate action plan. “We’re trying to address flooding the right way, but there are parameters the [Army Corps] designs that we cannot breach. When the federal government gives you $400 million, you don’t say no.”

Beyond catastrophic storm surges that the corp’s CSRM is designed to protect against, McClellan knows flooding is a real, everyday issue. On a sunny day with blue skies, she still has to reroute her car to avoid significant flooding. Her house was built in 1905 with a basement and first-floor elevation of six feet above ground. During the nor’easter storm in 2009, she had six inches of water in her basement.

“It’s coming up our storm drains instead of going out of our drains,” said the Superward 6 councilwoman. “Flood insurance rates are rising and causing people to no longer be able to stay in their house.”

McClellan has focused on flooding since 2016, with the Army Corps of Engineers and the CSRM. They finished the three-phase integrated feasibility report in 2019. The USACE had to then wait for appropriation.

“Typically, an appropriation from Congress happens after a major catastrophe,” said McClellan. “Our disaster was COVID.”

After COVID-19, Norfolk agreed to partner with the Army Corps in the 2.6 billion dollar project, with a commitment from the USACE to finish all five phases of the CSRM. However, there’s a catch. The project could take decades, and the federal government is only covering 65 percent of the funding. The Biden administration made a downpayment on the federal government’s $1.7 billion share in June 2023 when it announced that the Bipartisan Infrastructure law included an initial $399 million for the CSRM. The announcement included no mention of Justice40. That left Norfolk and local officials to come up with the remaining 35 percent of funds, or about $930 million, for CSRM.

“We’re trying to get the state to be a 50-50 partner with us,” said McClellan. “It will mean millions of dollars for Norfolk taxpayers in the future, but it’s mitigating future storm risks.”

FEMA says that for every dollar a Norfolk resident spends, they save between seven and ten dollars in post-disaster recovery costs. The councilwoman says it’s hard to communicate this to citizens without any immediate gratification.

“We can't tell citizens if we know when it is coming or how bad it is going to be,” said McClellan. “Especially when we need to improve our roads, schools, and public safety.”

Although engineers say the CSRM Project will save about 85 percent of Norfolk’s homes in future major storms. The councilwoman is aware of the anger from the remaining 15 percent.

“The Southside of Norfolk has rallied and said, ‘Hey, this isn’t fair because you left us out,’ and we’re trying to take that into consideration,” said McClellan. “I will say this problem is exacerbated because of the redlining that took place decades ago when cities like Norfolk would not put infrastructure in our poor, underserved minority communities.”

The Stain of Redlining

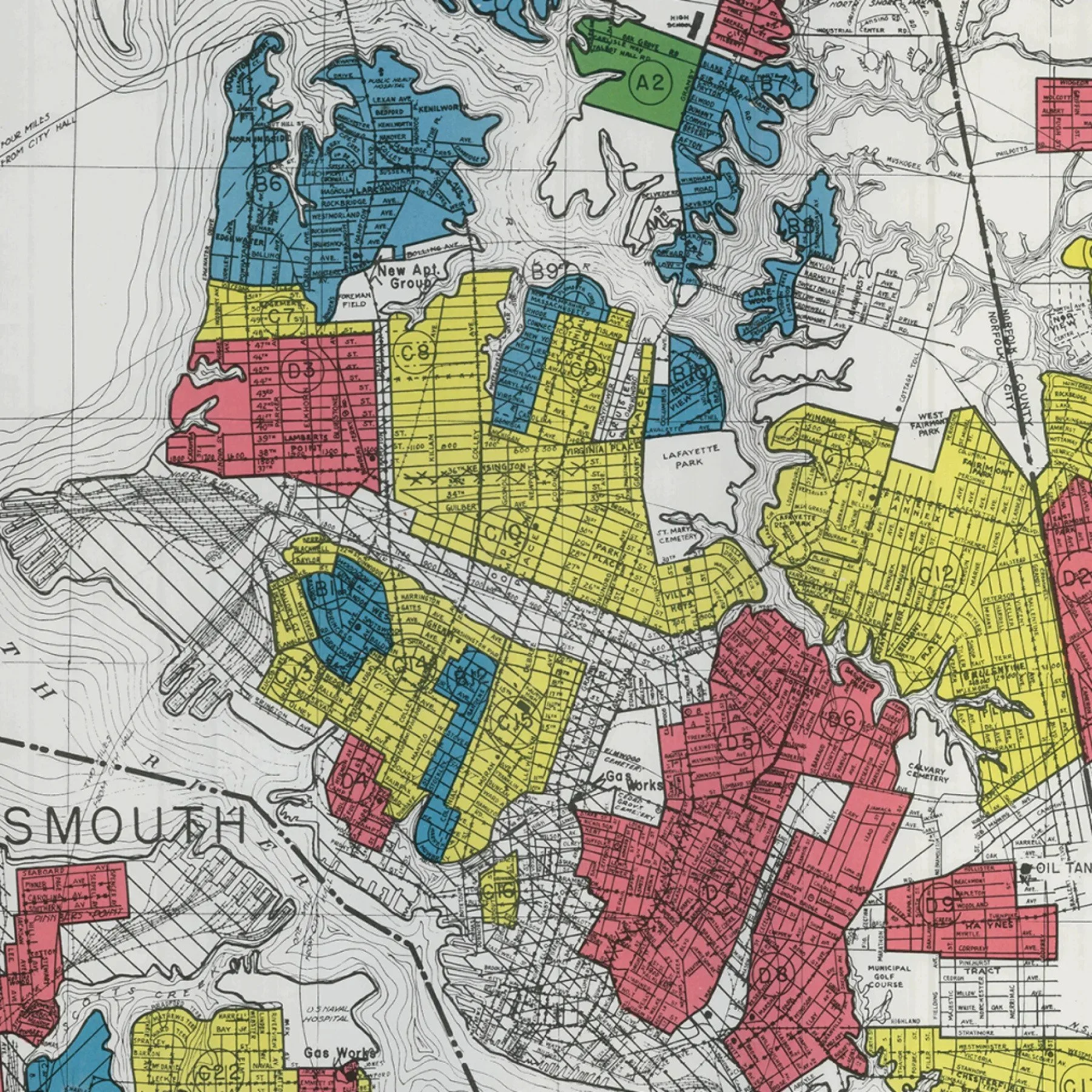

Properties are just not worth as much in some of the lowest housing communities like Berkeley compared to the rest of Norfolk due to a historically discriminatory practice called redlining.

“The Homeowners Loan Corporation creates maps that said the best neighborhoods were green and the bad neighborhoods, which had the most ‘negros,’ were red,” said Kim Sudderth. “That red color told the city to not invest.”

Redlining is a practice by banks and insurers to exclude minority homeowners from areas that became low-income in the 1920s and 1930s. The practice was banned with the Fair Housing Act of 1968. The effects remain and create stains of deep-rooted segregation, economic inequality, and lack of accessibility.

“We’re playing catch-up with our property value,” said Sudderth. “One injustice created another injustice and now it is environmental justice.”

The neighborhoods in Norfolk redlined in the 1940s are the most vulnerable to a health crisis and to flood risk. Councilwoman McClellan is correct. The disaster that caused the government to continue the CSRM was COVID, but the pandemic that should have caused them to act is redlining.

“You couldn't refinance your home to put your kid through college, so of course our homes would deteriorate. And it all just happens to be our black and brown communities now.”

Half of the redlined communities in Norfolk were African American: Berkeley, Campostella Heights, Calvert Square, Tidewater Gardens, Young Terrace, and more. The haunting legacy has caused the residents of these neighborhoods to live in the worst conditions.

“Now you don’t have the stormwater infrastructure to handle these massive rain events,” said McClellan. “So the flooding is even worse in those communities.”

Redlining has put Norfolk behind schedule. The climate change clock is ticking for the nation, the city of Norfolk, and black low-income communities. By the time the Army Corps of Engineers revisits its cost-benefit analysis, Norfolk raises enough money to expand its sunny day flood prevention projects, and the city meets its outreach obligations, will it be too late?

These obligations were among those that motivated Justice 40, the funding commitment intended to redress decades of underinvestment, discrimination, and, in some cases, the abandonment of minority communities. So, what happened?

A Lost Opportunity

The Biden administration established Justice40 in Executive Order 14008, but Sudderth said she has not seen a commitment to dedicating 40 percent of federal funding to Norfolk’s minority and disadvantaged communities.

While the Army Corps cites numerous programs as bound by the Justice40 requirements—among them flood and storm damage reduction programs, floodplain management services, and planning assistance to states—Sudderth said the corp’s CSRM for Norfolk excluded Berkley and the other predominantly Black Southside communities because their real estate was worth less than the cost of building the flood walls.

“It’s like they said, ‘It’s not worth protecting because the wall would cost more than the property,’” said Sudderth. “EJ40 should be eliminating that thinking from the decision-making process.”

Beyond the CSRM, Sudderth said EJ40 has not been applied to Norfolk.

For example, Community Benefits Plans are required for all Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) funding opportunity announcements by the Department of Energy. The plans are supposed to implement the Justice40 Initiative. As of this year, Norfolk has no Community Benefits Plan on the Department of Energy website.

“I don’t think so, not just yet,” said Sudderth. “This is an opportunity for the Corps to do environmental justice the right way and let Norfolk be an example to future projects.”

Environmental advocates, including Sudderth, have been working with the Corps since last March, trying to secure funding in Congress for the Southside feasibility study.

“That has not happened and communication has been poor,” said the community champion. “We recently had to raise our voices and say it is unacceptable.”

Outreach Is the Forgotten Solution

The city admits outreach was not a priority when the study began in 2016 and ended in 2019. When the BIL accelerated the process of approval and added funds to the pot, they decided to reach out to residents in the form of informational material and community meetings. The Office of Resilience in Norfolk, which oversees the CSRM, says it had estimated sixty to seventy community events.

“I’m not sure why they don’t know,” Kyle Spencer, Chief Officer of Resilience, told The Virginian-Pilot in August. “I think we’re doing our best to get it out there.”

In the article, Lawrence Brown, president of the Campostella Heights Civic League, begged to differ. “As my grandma used to say, we were bamboozled from the beginning,” the activist told the publication. Campostella Heights is one of the Southside communities not protected by the CSRM.

The problem lies with time. The meetings with the community started long after the city knew the Southside was not getting a wall. According to the Office of Resilience, the outreach meetings occurred this spring. The way community leaders found out about receiving no funding was a different story.

“I got a copy of an article saying, ‘Hey, you didn’t get funding,’” said Sudderth. “I was like ‘Why am I reading this?’ I sent it to Lawrence, and he had the same reaction.”

“It could have been easily dealt with by just coming up and saying, ‘Hey, we’ve run into a snag with funding. It may look like it’s going to be next year,” Brown told The Virginian-Pilot.

Outreach has been a problem for Norfolk in not only the recent USACE studies but the Tidewater Gardens transformation project. Michelle Cook, an environmental champion for Tidewater Gardens, passed away during the pandemic in May of 2020 fighting for inclusion.

Cook was the president of the Tidewater Gardens Tenant Management Corporation and served as a bridge between residents and the city. Before the city implemented the St. Paul’s Transformation Project, she and her community were left in the dark and concerned about what was next. Cook disproved the city moving forward with the project without properly seeing what the community wanted moving forward.

“Hello, excuse me. Everybody needs housing,” Cook said. “It just don’t make any sense to me to say you’re going to tear down housing and not replace what you take down.”

Within her worry about the future of her housing, she raised three boys. Cook had three jobs and ended up in public housing after developing a kidney disease.

“She was on her deathbed looking for a job because she knew she needed to find another place to live,” said Sudderth with tears streaming down her face. “Losing her was a blow.”

Michelle Cook’s story is one of many Black, low-income residents who move to public housing not knowing they are moving to an island. The city was completely out of reach. Although Norfolk reconciles the frustrations of Tidewater Garden residents by enlarging the number that can move into the new complex, nothing can make up for the lack of outreach that snowballs into another tragic story of homelessness.

“A lot of residents have the same story– ‘I gotta pay for medical drugs or pray for my rent and secure my living place,” said Stiles as he looked at Kim Sudderth with empathy. “It really could have been sitting down one unit at a time and saying let’s figure this out. It’s not fair at all.”

Despite the mountain of sad stories because of neglect, these activists still have hope and won’t stop demanding inclusion.

“I can't tell your story better than you, and you can't tell your story better than me,” said Sudderth. “So if you're going to tell my story, you should probably include me in the meeting. When it’s time to talk to Congress, we should be in the room.”

Sudderth wants to bring her porch culture, redlining, property values, and equitable climate resilience to the table of Congress.

The south side of Norfolk is just waiting for the invite.

A Race Against the Climate Clock

The beloved community called Berkley was founded in 1890 by an Act of Assembly. In the southeastern corner of Norfolk lies Campostella since the early 20th century. Calvert Square was named after a street within the community and was founded in 1957. When the floods came and the city offered them nothing but elevating their homes, they knew this was going to be yet another problem to conquer.

“I think about Hurricane Harvey in Houston and how it just stayed over them and churned for days,” said Gayden. “My fear is that this is what could happen here to us. So I do believe our communities are worth fighting for.”

There is a contradiction of disappointment and blind hope from the south side of Norfolk. The exclusion from the Army Corps of Engineers Coastal Storm Risk Management Project is not a surprise but a signal that it is time for them to fight back.

“We understand this is a steep learning curve,” said Sudderth in exasperation. “But we care enough to walk this with you.”

How many steps can you take when the person beside you isn’t walking, too?

“We’re currently on the board, but we’re not even sure what is going to happen next.”

Kim Sudderth looks across the calm waters of the Elizabeth River at Downtown Norfolk, the city that will be receiving a fortified wall to protect it from the dangers of the uncertainty that is climate change. She has room for understanding.

“Our office of resilience is caught in the middle and working with what they learn, which is also pretty late. With the USACE, there is no wiggle room, let alone Congress. Some of them may want to do something now but are also stuck now.”

And time has no room to wait.

“But that’s all we can do,” said Kim Sudderth. “Wait to see how things shake out here in Norfolk. As soon as I know, I’ll let you know.”

She wishes Norfolk would have done the same.

References2, ished J. (n.d.). Redlining. Federal Reserve History. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/redliningBerkeley Plantation. (n.d.-a). https://www.virginia.org/listing/berkeley-plantation/4889/Bohon, A. (2024, September 17). Norfolk residents to meet Wednesday with a focus on $2.6 billion flood project. News 3 WTKR Norfolk. https://www.wtkr.com/news/in-the-community/norfolk/norfolk-residents-to-meet-wednesday-with-a-focus-on-2-6-billion-flood-projectDaylighting rivers and streams. Naturally Resilient Communities. (n.d.). https://nrcsolutions.org/daylighting-rivers/#:~:text=Daylighting%20rivers%20or%20streams%20is,them%20to%20their%20previous%20condition.Disaster relief appropriations. (n.d.-b). https://www.congress.gov/113/plaws/publ2/PLAW-113publ2.pdfFinn, J. C., & Online, P. (2019, August 5). John C. Finn: Promise of fair housing act still unfulfilled 50 years later. Pilot. https://www.pilotonline.com/2018/04/29/john-c-finn-promise-of-fair-housing-act-still-unfulfilled-50-years-later-2/GovTech. (2023, June 26). How Norfolk residents fought discriminatory flood policies. GovTech. https://www.govtech.com/em/safety/how-norfolk-residents-fought-discriminatory-flood-policiesHafner, K. (2024, July 18). Norfolk’s Army Corps can’t yet study extending floodwall to southside communities. WHRO Public Media. https://www.whro.org/environment/2024-07-18/norfolks-army-corps-cant-yet-study-extending-floodwall-to-southside-communitiesHome elevation for flooding. Home elevation for flooding | Hampton, VA - Official Website. (n.d.). https://hampton.gov/3334/Home-elevation#:~:text=Home%20elevation%20program%20can%20help,the%20cost%2C%20plus%20temporary%20relocation.Justice40 Initiative | Department of Energy. (n.d.-c). https://www.energy.gov/justice/justice40-initiativeMitigation saves fact sheet - FEMA. (n.d.-d). https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-07/fema_mitsaves-factsheet_2018.pdfNoe, E. (2023, March 16). Residents of historically black neighborhoods on Norfolk’s Southside concerned about proposed Floodwall Project. Pilot. https://www.pilotonline.com/2023/03/15/residents-of-historically-black-neighborhoods-on-norfolks-southside-concerned-about-proposed-floodwall-project/Norfolk Coastal Storm Risk Management (CSRM) project. Norfolk Coastal Storm Risk Management (CSRM) Project | City of Norfolk, Virginia - Official Website. (n.d.). https://www.norfolk.gov/5282/Norfolk-Coastal-Storm-Risk-Management-CSNorfolk Coastal Storm Risk Management Feasibility Study. Norfolk District. (2018, March 21). https://www.nao.usace.army.mil/NCSRM/Redlining health: Comparing Norfolk redlining and vulnerability maps. The Urban Renewal Center. (n.d.). https://theurcnorfolk.com/redlining-vulnerability-infection-mapsThe ripple effect: Award-winning flood visualization tool available... City of Virginia Beach. (n.d.). https://virginiabeach.gov/connect/blog/award-winning-flood-visualization-tool-available-for-residents-to-see-impact-of-shore-drive-projectStatic1.squarespace.com. (n.d.-e). https://economistsview.typepad.com/.a/6a00d83451b33869e201b7c80248f3970b-popupThe United States Government. (2024, February 28). Justice40 initiative. The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/environmentaljustice/justice40/Webmaster, N. (2020, November 2). Home - st paul’s transformation project. St Paul’s Transformation Project - Reimagine and revitalize the Tidewater Gardens community. https://stpaulsdistrict.org/WHRO | By Katherine Hafner. (2024a, May 6). As Norfolk Eyes $2.6 billion project including floodwall, many are concerned what - and who - is not included. WHRO Public Media. https://www.whro.org/2023-03-27/as-norfolk-eyes-2-6-billion-project-including-floodwall-many-are-concerned-what-and-who-is-not-includedWHRO | By Katherine Hafner. (2024b, October 3). “Fixing what’s broken”: Norfolk Community leaders meet with EPA to discuss environmental justice. WHRO Public Media. https://www.whro.org/environment/2024-10-03/fixing-whats-broken-norfolk-community-leaders-meet-with-epa-to-discuss-environmental-justiceWHRO | By Ryan Murphy. (2024, June 24). “we’re planning to plan”: Norfolk’s Housing Authority starts early discussions on redeveloping two more public housing communities downtown. WHRO Public Media. https://www.whro.org/business-growth/2024-06-24/were-planning-to-plan-norfolks-housing-authority-starts-early-discussions-on-redeveloping-two-more-public-housing-communities-downtown